Research Article - Modern Phytomorphology ( 2025) Volume 19, Issue 6

Determination of antioxidant activity of some commercial plant essential oils in Saudi Arabia markets

Salah E. M. Abo-Aba1,3*, Hussein R. M2, Nadiah Al-Sulami1 and Othman Y. Alyahyawy42Department of Genetics and Cytology, Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Institute, National Research Center, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt

3Princess Dr. Najla Bint Saudi Al-Saud for Excellence Research in Biotechnology, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4Department of Medical Laboratory Technology (MLT), Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdul-Aziz University, Rabigh, Saudi Arabia

Salah E. M. Abo-Aba, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University (KAU), P.O. Box 80141, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia, Email: info@paperlyst.co.in

Received: 17-Nov-2025, Manuscript No. mp-25-174116; , Pre QC No. mp-25-174116 (PQ); Editor assigned: 19-Nov-2025, Pre QC No. mp-25-174116 (PQ); Reviewed: 03-Dec-2025, QC No. mp-25-174116; Revised: 15-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. mp-25-174116 (R); Published: 22-Dec-2025, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.18295956

Abstract

Commercial plant essential oils have been widely studied for antioxidant activities as substitutes for artificial preservatives in food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. The antioxidant properties of the commercial essential oils sourced in Saudi Arabia (specifically Cinnamon (Cin) (Cinnamomum verum), Fennel (Fen) (Foeniculum vulgare L.), Thymus (Thy) (Thymus camphoratus), and Pomegranate (Pom) (Punica granatum)) were examined in the present study. These oils were extracted in vitro utilizing ethanol, hexane, and water in spectrophotometrically analysed methods to evaluate TLAC and TWAC. Out of all solvents, ethanol-extracted Cinnamon oil has the highest antioxidant activity while the Thy, Fen, and Pom oils have lower levels across all solvents. These findings reinforce the ability to determine the effective doses of natural preservatives and functional ingredients that exhibit high antioxidant activity and demonstrate that efficacy is a function of the compound concentration and specificity to each oil. The findings underscore the significance for future research to clarify the role of essential oils beyond their food components in various health-related applications due to their antioxidant activity.

Keywords

Antioxidant, Essential oils, Cinnamon, Fennel, Pomegranate, Thymus, Phenolic compounds, Free radical scavenging, Natural antioxidants, Plant extracts

Introduction

Essential or volatile oils (e.g. aromatic liquids) are oils which are concentrated and aromatic liquids containing a variety of volatile compounds. These fragrant oils come from plants based on leaves, flowers, buds, seeds, roots and pericarps. They are rich sources of a plethora of bioactive agents present that exhibit antioxidative and antimicrobial properties (Cassel and Vargas 2006, Di Leo Lira, et al. 2009). The composition varies from plant to plant, especially aromatic, leading to different colours and smells depending on their constituents. The yield of these oils is also significantly variable with various plant species, thus affecting the market rates based on the supply of these oils (Bousbia, et al. 2009). Some bioactive compounds such as cinnamaldehyde in cinnamon and carvacrol in thyme oil have been reported to possess potential antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens based on their natural activities (Llana-Ruiz-Cabello, et al. 2015). Well characterized ingredients in these oils may potentially be used as natural replacements for food safety and shelf life in preserving processes (Mith, et al. 2014). In these essentials are cinnamon, thyme, clove, sage, rosemary, and vanillin with established efficacy against bacterial strains.

Because of their strong antioxidant capacities that minimize the risks of diseases, play the part in reducing CVD, cancer development, inflammation, and other adverse conditions from harmful free radicals generated by cellular reactions (Kumar, et al. 2019). A wide range of health benefits from natural plants are available. This work aims to study how these compounds can act upon the antioxidant properties of these oils as chemical neutralizing factors to counteract the formation of cellular forms of harmful free radicals and lead to protective effect against CVD risk to mitigate these harmful free radical formation in humans (Kumar, et al. 2019). According to study by Smail, et al. 2011, Imane, et al. 2020 identified phenolic compounds present in certain extracts of plants as powerful antioxidant compounds.

The study of Khalil and Ahmed, 2024 on the physical and chemical properties of clove thyme marjoram antioxidants through gas chromatography/mass spectrometry proved advantageous. Free radical scavenging capabilities and reduction capacities were identified in three major components under study. The extracts of citrus cultivars produced from another study by Yang and Park, 2004 showed that they had better antioxidant activity than the other varieties. Chronic diseases can largely blame oxidative damages in lipids, proteins, nucleic acids caused by free radicals’ actions, as many findings have shown (Langseth, 2000). Among the many studies, a common goal have been to analyze the beneficial effects of dietary antioxidants. Spices herbs are identified as important natural sources of antibacterial and antioxidant compounds; their efficacy is largely ascribed to their polar phenolic compounds and essential oils (Santoyo, et al. 2006, Elmastas, et al. 2006, Pillai and Ramaswamy 2011). In this study, it was aimed to evaluate potential antibacterial antioxidative effects of selected commercial plant essential oils.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

Commercial plants: The essential oils of four medicinal plants were Cinnamon (Cin) (Cinnamomum verum) from the Lauraceae family, Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) from the Apiaceae family, Thymus (Thymus camphoratus) from the Lamiaceae family, and Pomegranate (Punica granatum) from the Lythraceae family sourced from herbal product retailers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Determination of antioxidant activity

Preparation of ethanol, hexane and water utilized stock solutions consisting of α-tocopherol and L-ascorbic acid and evaluated spectrophotometrically at 294 nm, in accordance with the method described by Windholz, 1976. Essential oil extracts were stored at temperatures around 4°C prior to adding either hexane, ethanol, or water at ratios of approximately two milliliters per gram homogenizing suspensions, then transferred into glass tubes where they were shaken for 1 hour under dark conditions at low temperatures, and centrifuged at high speed, allowing for supernatants to be evaluated following Alshehri, et al. 2019 research methodology first developed.

TLAC determination

The total antioxidant capacity of plant extracts of the essential oils was measured spectrophotometrically as reported by Prieto, et al. 1999 and is based on the formation of blue-green phosphomolybdenum complexes. Total lipid-soluble antioxidants of the hexanic extract were tested by mixing 5–200 μL of hexanic extract with 1 mL of phosphomolybdenum reagent (32 mM sodium phosphate, 4 mM ammonium molybdate, and 0.6 M sulfuric acid). They stirred the mixture and incubated it at 95°C (> 90 minutes). First, researchers used absolute ethanol to perform control reactions, followed by absorbance measurements at 695 nm. They expressed TLAC as a function of α-tocopherol concentration and created standard curves (A695 vs. μM α-tocopherol) from various concentrations in ethanol. They quantified average extinction coefficient (ε) of 137 μM- ¹ (r²=0.9998). Lastly, TLAC was determined per gram of plant material in terms of the following equation:

TLAC (μmol α-tocoferol/g)=A695 × E−1 × RV × SV−1 × EV × m−1.

A695=Absorbance at 695 nm; E−1=Absolute inverse extinction coefficient (137 μM−1); RV=Overall reaction volume; SV=Sample volume used in the reaction; EV=Solvent volume; and m=Amount (grams) of fresh plant material extracted.

Using TLAC37 (37°C) rather than 95°C yielded a greater overall antioxidant capacity resulting from potent lipid-soluble antioxidants (Prieto et al., 1999). All measurements were taken in triplicate.

TWAC determination

Water extracts (5–200 μL) were added to 1 mL of phosphomolybdenum reagent, the mixture was agitated and incubated at 95°C for 90 minutes. As a control for the experiments, the researchers utilized pure water and measured the absorbance at 695 nm. TWAC was expressed as the equivalent of L-ascorbic acid. Standard curves (A695 vs. μM L-ascorbic acid) were created by dissolving L-ascorbic acid at various concentrations in water, and the extinction coefficient was determined as 213 μM- ¹ (r²=0.9996). The TWAC per gram of fresh plant material was calculated with the formula:

TWAC (μmol L-ascorbic acid/g)=A695 × E−1 × RV × SV−1 × EV × m−1.

For our tests at 37°C (TWAC 37) and not 95°C, we measured total antioxidant capacity, as these are high water-soluble antioxidants (Prieto, et al. 1999). All were made in triplicate.

Results and Discussion

The antioxidant potential of extract of cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and pomegranate (Punica granatum) depended heavily on the solvent used (ethanol, hexane, or water); polar solvents tended to be the more active solvent since phenolic compounds and flavonoids can be extracted more efficiently using solvent. Some extracts exhibited the strongest antioxidant activity by aqueous extracts while other extracts were less effective, it could be attributed to the low solubility of polar antioxidants. The conclusions highlight the significance of solvent selection in enhancing antioxidant extraction in functional foods, pharmaceuticals, and natural preservatives.

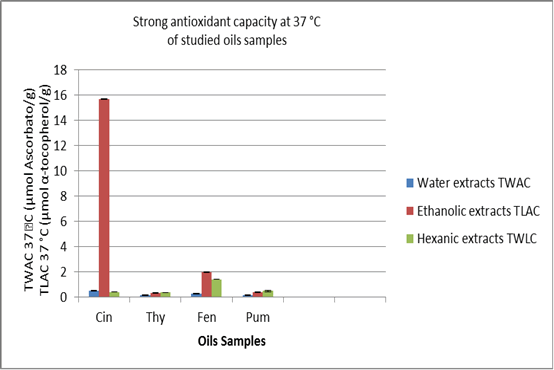

The analysis addressed both strong water-soluble and lipid-soluble antioxidants. Figures include the TWAC37 and TLAC37 values associated with strong water-soluble antioxidants and strong lipid-soluble antioxidants of type ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol. As shown in Fig. 1, extracts from the essential oils of chosen herbs exhibited mixed potent antioxidant activity in TWAC37 and TLAC37. The activity of cinnamon oil isolated from ethanol was the highest in terms of antioxidants. This aligns with some previous research indicating that cinnamon improves antioxidant action (Shan, et al. 2005, Rousse, et al. 2009, Noorolahi, et al. 2012). Thyme, fennel, and pumpkin oils showed significantly less antioxidant activities for the three solvents evaluated (water, ethanol, and hexane), contrasting with previous researches (Mohamed,et al.2007).The discrepancy canbe attributed to the decreasedconcentrationof potent antioxidant chemicals in some products as a result of the extraction procedures of specific herbalists using essential oils. Consequently, aqueous extracts showed reduced antioxidant activity for all the commercial essential oils screened, indicating that water is a poor choice as solvent in extracting antioxidant compounds from it.

Figure 1. Analysis of the antioxidant capacity in of oil extracts: Data represent means of three independent determinations ± SD and concentrations are relative to their weights. Expressed TWAC37 are equivalent to L-ascorbic acid (µm /gm) and TLAC37 to α-tocopherol (µm/gm).

Total water-soluble and lipid soluble antioxidants capacity

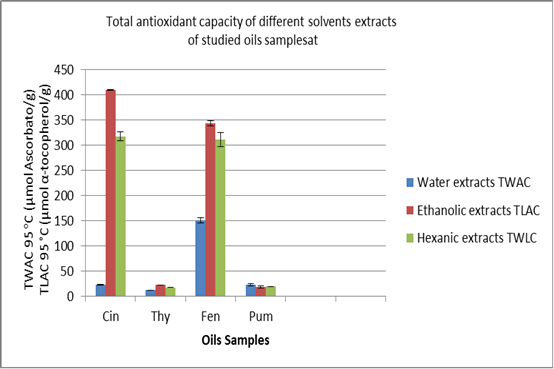

Results of TWAC and TLAC of the four extracts using multiple solvents, including water, ethanol, and hexane, are presented in Fig. 2. The Cin and Fen commercial oils exhibited high total antioxidant activity, notably when first extracted with ethanol, then with hexane (Shan, et al. 2005, Rousse, et al. 2009, Noorolahi, et al. 2012). Results showed extracts with water remain inconsistent with previous data on the plant material (Sacchetti, et al. 2005, Singh, et al. 2007, Mohamed, et al. 2007). Ethanol would be the most suitable solvent for the extraction and Thy, Pum showed low antioxidant activity on comparision with Cin and Fen.

Figure 2. Comparaitive determination of antioxidant capacity of various extracts: Data represented as means ± SD and concentrations are relative to their weights. Expressed TWAC are equivalent to L-ascorbic acid (µm per gram) and TLAC to α-tocopherol (µ per gram).

Conclusions

The antioxidant potential of extract of cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and pomegranate (Punica granatum) depended heavily on the solvent used (ethanol, hexane, or water); polar solvents tended to be the more active solvent since phenolic compounds and flavonoids can be extracted more efficiently using solvent. Some extracts exhibited the strongest antioxidant activity by aqueous extracts while other extracts were less effective, it could be attributed to the low solubility of polar antioxidants. The conclusions highlight the significance of solvent selection in enhancing antioxidant extraction in functional foods, pharmaceuticals, and natural preservatives.

References

- Casse IE, Vargas RMF. (2006). Experiments and modelng of the Cymbopogon winterianus essential oil extraction by steam distillation. J Mexican Chem Soc. 50:126–129.

- Di Leo Lira P, Retta D, Tkacik E, Ringuelet J, Coussio JD, van Baren C, Bandoni AL. (2009). Essential oil and by-products of distillation of bay leaves (Laurus nobilis L.) from Argentina. Ind Crops Prod. 30:259–264.

- Bousbia N, Abert Vian M, Ferhat MA, Petitcolas E, Meklati BY, Chemat F. (2009). Comparison of two isolation methods for essential oil from rosemary leaves: Hydrodistillation and microwave hydrodifusion and gravity. Food Chem. 114:355–362.

- Llana-Ruiz-Cabello M, Pichardo S, Maisanaba S, Puerto M, Prieto AI, Gutiérrez-Praena D, Jos A, Cameán AM. (2015). In vitro toxicological evaluation of essential oils and their main compounds used in active food packaging: A review. Food Chem Toxicol. 81:9–27.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mith H, Dure R, Delcenserie V, Zhiri A, Daube G, Clinquart A. (2014). Antimicrobial activities of commercial essential oils and their components against foodâborne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria. Food Sci Nutr. 2:403–416.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar V, Mathela CS, Kumar M, Tewari G. (2019). Antioxidant potential of essential oils from some Himalayan Asteraceae and Lamiaceae species. Med Drug Discov. 1:100004.

[Crossref]

- Smail A, Lyoussi B, Miguel M (2011). Antioxidant and Antiacetylcholinesterase activities of some commercial essential oils and their major compounds. Molecules. 19:7672–7690.

- Imane NR, Fouzia H, Azzahra LF, Errami Ahmed E, Ismail G, Idrissa D, Mohamed KH, Sirine F, L’Houcine O, Noureddine B. (2020). Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of some essential oils against multidrug resistant bacteria. Eur J Integr Med. 35:101074.

[Crossref]

- Khalil GA, Ahmed HA. (2024). The antioxidant activity and chemical properties of three essential oils that are grown in Egypt. Menoufia J Agric Biotechnol. 9:95–107.

- Yang J, Park M. (2024). Antioxidant effects of essential oils from the peels of Citrus cultivars. Molecules. 30:1–15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Langseth L. (2000). Oxidants, antioxidants, and disease prevention. ILSI Europe Press.

- Santoyo S, Lloría R, Jaime L, Ibañez E, Señoráns FJ, Reglero G. (2006). Supercritical fluid extraction of antioxidant and antimicrobial compounds from Laurus nobilis L. Chemical and Functional Characterization. Eur Food Res Technol. 222:565–571.

- Elmastas M, Gülçin Ä°, IÅıldak Ö, KüfrevioÄlu ÖÄ°, Ä°baoÄlu K, Aboul-Enein HY. (2006). Antioxidant capacity of bay (Laurus nobilis L.) leave extracts. J Iran Chem Soc. 3:258–266.

- Pillai P, Ramaswamy K. (2011). Effect of naturally occuring antimicrobials and hemical preservatives on the growth of Aspercillus parasiticus. J Food Sci Technol. 49:228–233

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Windholz M, Budavari S, Stroumtsos LY, Fertig MN. (1976). The Merck index. An encyclopedia of chemicals and drugs.

- Alshehri MH, Aldhebiani AY, Hussein RM. (2019). Comparative study of antioxidant activity of some medicinal plants belonging to Lamiaceae and Apiaceae from Al-Baha region, Saudi Arabia. Res J Biotechnol. 14:71–78.

- Prieto P, Pineda M, Aguilar M. (1999). Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: Specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal Biochem. 269:337–341.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shan B, Cai YZ, Sun M, Corke H. (2005). Antioxidant capacity of 26 spice extracts and characterization of their phenolic constituents. J Agric Food Chem. 53:7749–7759.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roussel AM, Hininger I, Benaraba R, Ziegenfuss TN, Anderson RA. (2009). Antioxidant effects of a cinnamon extract in people with impaired fasting glucose that are overweight or obese. J Am Coll Nutr. 28:16–21.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noorolahi Z, Sahari MA, Barzegar M, Doraki N, Naghdi Badi H. (2012). Evaluation antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of cinnamon essential oil and Echinacea extract in Kolompe. J Med Plants. 12:14–28.

- Mohamed R, Pineda M, Aguilar M. (2007). Antioxidant capacity of extracts from wild and crop plants of the Mediterranean region. J Food Sci. 72:59–63.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sacchetti G, Maietti S, Muzzoli M, Scaglianti M, Manfredini S, Radice M, Bruni R. (2005). Comparative evaluation of 11 essential oils of different origin as functional antioxidants, antiradicals and antimicrobials in foods. Food Chem. 91:621–632.

- Singh G, Maurya S, Marimuthu P, Murali HS, Bawa AS. (2007). Antioxidant and antibacterial investigation on essential oils and acetone extracts of some spices. Nat Prod Radiance. 6:114–121.